Chinese medicine practitioners (myself included) regularly boast the lengthy history of our medicine. Whilst it is truly ancient, old doesn’t automatically mean good. Often what is old is simply out dated and there may be other, better, more modern, options.

Take “Western” medicine as an example. What is practised today is very different from the ancient Greek medicine of Hippocrates. Western medicine, too, began with the use of plant, animal and mineral substances, but very few of those medicines are still in mainstream use.

For Western medicine, time has brought an improved understanding of anatomy, physiology and pathology, and therapeutic practices, sometimes from as recent as 10 years ago, are considered out dated and have been improved upon.

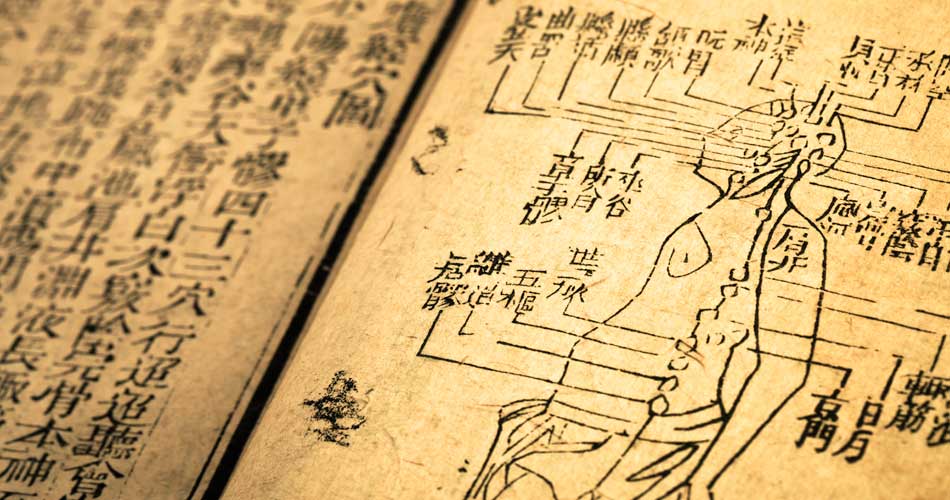

Why isn’t this the same for ancient Chinese medicine? Chinese medical theory and practice has certainly evolved over the last 2000-3000 years, however still today, the authoritative theoretical texts are ones that were written between 1800 and 2400 years ago (during the Warring States period and the Han dynasty).

The core theories of Yin and Yang and five elements, from this period, have been the base theories of just about every school and branch of Chinese medicine since. They are certainly the basis of contemporary traditional Chinese medicine.

One classical text, from the same period, is the Shang Han Za Bing Lun – Treatise On Cold damage and Complex Disease. This book of herbal prescriptions is still taught heavily to students of Chinese medicine in universities around the world. It is so complete that it is quite acceptable, and quite possible, to practise using only prescriptions from this text.

Why haven’t we moved on? How can these treatments be relevant to modern diseases, many of which didn’t exist at the time?

The answer lies in the nature of the theoretical framework of ancient Chinese medicine. To explain health and disease, and the ways in which we are influenced by the world around us, some very big, abstract and therefore malleable concepts are used – concepts like Yin/Yang and five element theory.

Chinese medicine, especially ancient Chinese medicine, is more concerned with function rather than matter. The internal organs, for example, are theoretical units that interact and maintain balance with each other, rather than physical entities. These flexible concepts allow the medicine to adapt to new illnesses. A new illness is still a breakdown of normal physiology, and there are a finite number of possibilities for poor physiology.

When it comes to treatment, the big difference between Chinese medicine and modern Western medicine is, very broadly speaking, Western medicine tends to take a more allopathic approach. It wants to isolate and directly oppose a pathology (eg a laxative for constipation), whereas Chinese medicine seeks to correct pathology by encouraging normal physiology (eg ensuring the bowels are adequately lubricated and moistened).

An allopathic approach often requires new treatments as new illnesses arise. With the classical Chinese medicine approach, because we are looking to restore balance between the internal organ systems, and because other illnesses can display with a similar imbalance, we know what to do.

When you know the theoretical base and the treatment models of a medicine are sound (that is, when they are used correctly, they are effective) and the system naturally allows a good degree of flexibility, more time means more experience with its use.

Generation after generation of doctors, treating literally billions of patients, have recorded their experiences with the use of this medicine and passed them on to the next generation. If a medicine can survive 2000 years of peer review, which within China is known to have been particularly tough, then it can only be considered highly relevant.